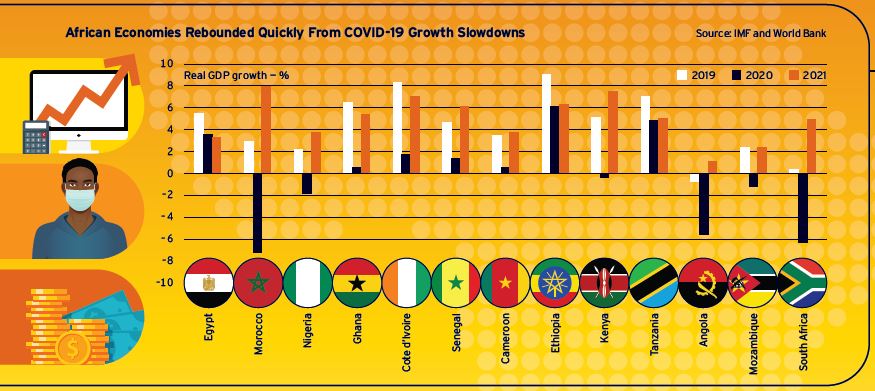

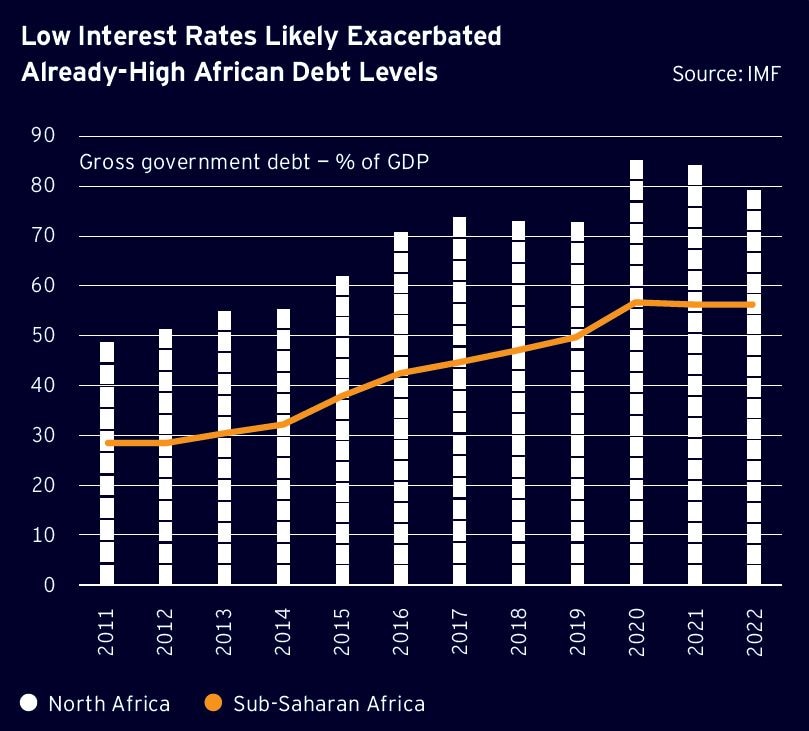

Although, broadly speaking, Africa rode out the pandemic-related economic crisis relatively well, with growth slowing much less than most economists forecast, the crisis has brought to a head many issues that were already emerging. Notably, following COVID-19, and then the rise in international interest rates, the widening fiscal deficits have proved hard to fund and led to defaults in Zambia and Ghana.

But COVID-19 also highlighted the ongoing resilience of the growth story in Africa, which seems to have firmly put a floor on growth in many countries. The pandemic also underscored the importance of the informal sector as a safety net for many individuals and households across the continent. Not only has growth held up remarkably well, but there has been no wider spreading of defaults either. Yet the challenge facing the continent’s policymakers in the short term is clear: the need to narrow fiscal deficits. At present, this is set to be achieved under a new wave of International Monetary Fund (IMF) programs, which we have broadly dubbed the “New Age of Fiscal Austerity.”

Unlike in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the new wave of IMF programs is not based on cutting spending; in fact, spending on health and education will be preserved. Instead, fiscal consolidation is largely driven by raising revenue. A key element of this will be taxing the informal sector. Coupled with this is the challenge to formulate new exchange rate policies in an era of higher global interest rates.

It is also worth highlighting that after the last wave of defaults across Africa in the mid-1990s, better fiscal discipline and more flexible exchange rate regimes ushered in a strong pickup in growth, eventually encapsulated in the “Africa Rising” story. We think that at the time the hype around this story was overplayed, but that does not mean that there were not many real elements to it that still have important implications about how Africa will grow and develop going forward, or which we think will be the key elements of a “New Growth Model” for Africa.

For a “New Growth Model” to emerge, however, African governments, and the private sector are going to have to work together to take advantage of the continent’s favorable demographics, technological developments, and a changing world economy. At the same time, it is critical to avoid getting caught up in a new hype and forgetting the importance of developing foundational infrastructure.

There is an argument that politics could yet undermine such a “New Growth Model” playing out. While we accept that politics can be a constraint on development, we suspect that if the story is to play out as we hope, more African governments will simply have to get serious about economic growth and development as their central political and policy concerns.

Finally, it is important to bear in mind that development does require clear politics and policy, but also has an element of luck. Moreover, it is perhaps a much more gradual process than is often popularly perceived. Africa has changed vastly in the last 50 years and will continue to change. The challenge for policymakers, facing young and demanding populations, is to try and speed up the process.

African Economies Have Unique Strengths…

African economies have shown comparative resilience in the face of shocks such as the Global Financial Crisis and COVID-19 pandemic. This suggests their dependence on the informal and agricultural sectors is not always a negative. In our view, it implies a clear growth floor for most of the continent.

…and Vulnerabilities

The fiscal positions of many African countries were deteriorating before 2020, but low interest rates incentivized further excessive borrowing. Africa’s key policy battles in the coming years look set to center on improving fiscal discipline while also making exchange rate policy more flexible.

Can Growth by Trumped by Demographic Challenges?

It is uncertain whether Africa will be able to create the jobs necessary to absorb the inevitable rise in its labor force due to its rapidly growing population. On the other hand, aging populations elsewhere may create an historically unprecedented opportunity for the continent to become a global supplier of labor.

A New Growth Model

We identify the following strategies — all, of course, easier said than done —for African economies to maintain stable growth and improve their fiscal positioning: